Thursday, August 19, 1999

By LISA STIFFLER

SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTER

Sickened by pesticides, weakened by headaches and panic attacks, Don Paladin has turned his bedroom, with its stainless steel walls and spotless tiled floor, into a sanctuary.

Inside, he is safe from the chemicals that have turned his life upside down and left him weak, sick, wary and frustrated.

Frustrated because his friends, co-workers and neighbors don't understand that he suffers from an enigmatic and controversial disorder called Multiple Chemical Sensitivity.

The disorder is sometimes dismissed as being imagined by a patient. But sufferers disagree.

"If you don't fit into one of the three camps -- cancer, infection or allergies, what do you have left -- psychological," said Paladin, a former Whatcom County elementary school special education teacher who took a disability retirement in 1996 because of his poor health.

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, or MCS, strikes without warning and sufferers say it can cause chronic fatigue, aching head and joints, memory loss, chest pain, upset stomach and burning eyes and skin. It is said to be an incurable affliction that some doctors question the very existence of while others have tried to treat, without much success. There is no definitive cause of the disorder other than sufferers who complain of poisoning from the surrounding environment.

"It's definitely on the fringe for being accepted," said Dr. William Robertson, director of the Washington Poison Center in Seattle.

MCS patients claim that everyday household chemicals such as paint, perfume and cleaning products, as well as road tar, copy machines and industrial air pollutants make them sick.

Robertson doesn't deny that chemical odors can induce a sensation in people, but he questions if they can cause the symptoms reported with MCS.

"The mechanism (for the symptoms) can be psychology or physical," he said. But there is no evidence of molecular, physical changes caused by chemical exposure, he added.

This explanation is discouraging for MCS patients.

"It's sad that people are treated this way without anyone taking them seriously," Paladin said. "You wouldn't believe the devastation of people's lives."

Dr. David Buscher works with Paladin and other MCS patients at the Northwest Center for Environmental Medicine in Bellevue. He said the medical community has been slow to accept the disorder because it has only recently been identified and is absent from the curriculum of most medical schools.

"People have a hard time changing," he said. But doctors are "seeing so much of it (MCS), it's hard to deny it."

In 1998 the federal government finished drafting a report to define MCS, but widespread criticism has made reaching agreement over the disorder difficult. The group, with representatives from eight federal agencies, plans to reconvene this month to review comments on the draft and decide how to proceed.

A separate group of 34 researchers and doctors reached a consensus defining MCS, published earlier this summer in the international journal, "Archives of Environmental Health."

Opinions differ on when descriptions of MCS-like symptoms began emerging -- some say 40 years ago, others 100. But in the past decade it has received added attention with the prominence of Gulf War Syndrome suffered by Persian Gulf War veterans and because of increased reports of people made ill by so-called sick buildings.

Sufferers of both ailments can exhibit MCS-like symptoms, but symptoms from the latter appear short lived. The illness caused by sick buildings is only experienced while inside the building. Poor air quality, workplace stress and toxic chemicals have been suggested as causes.

Surveys conducted in the mid-1990s by New Mexico and California state health departments have found that between 2 percent and 6 percent, respectively, of the general population said they had MCS and that 16 percent of those surveyed claimed they are unusually sensitive to everyday chemicals.

Studies also find that women are more often afflicted, comprising 80 percent of sufferers.

Washington has not been surveyed for MCS, but Karen McDonell, an MCS patient living in Gig Harbor, maintains a state list of sufferers and has collected more than 900 names during the past six years. She said there are even more people in the state who are not on her registry, which only contains names of people contacting MCS support groups.

Pesticides seem to be one of the more reactive chemical cocktails that can drop MCS sufferers in their tracks. In Washington state, the Department of Agriculture keeps a list of people who have doctor verification of pesticide sensitivities. There are 42 residents of King, Pierce and Snohomish counties on the list and more than 100 residents statewide.

While scientists, doctors and non-profit groups continue to explore and debate the issue, MCS patients try to find ways of existing in a world suffused with approximately 40,000 chemicals blended into more than 2 million mixtures, many of unknown toxicity, according to the 1998 book "Neuropsychological Toxicology."

Individuals with MCS generally trace the start of their illness to a massive chemical exposure or repeat exposures.

Nancy Morris attributes her severe asthma, and ultimately

MCS, to contact with the pesticide 2,4-D as an infant. Her father used

the herbicide as a weed control for local wheat farmers. When he came home

from the fields the toxic pesticide came with him.

|

Now in her late 40s, Morris said she is still plagued by

pesticides. Her neighbors on a quiet street in Richmond Beach have their

yards regularly sprayed for bugs and weeds and have ignored her pleas to

stop. She's even offered to pay the difference for less toxic pest control.

"It doesn't register with them the concerns I have to deal with," Morris said. She blames their continued pesticide use on their lack of understanding of the chemicals' dangers. "They feel like because it's legal it's OK," she said. "But there is

so much new information that this is not OK . . . and I don't think anyone

should be put at risk in this way.

|

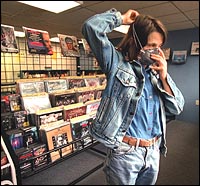

| Plagued by asthma and a severe sentitivity to chemicals, Nancy Morris must take protective measures such as wearing a mask just to go to a video store. Rick Giase/PI | "Besides, why care so much if you have dandelions or not?" |

Morris has traveled out of the Seattle area only three times in the past six years because of her affliction.

While Morris and Paladin say they are made ill by pesticides, others argue that the chemicals are perfectly safe when used properly.

Robertson recommends responsible, discretionary use of pesticides, suggesting people "choose their enemies carefully."

He dispels concerns about pesticide use at low levels.

"In the wrong doses, any chemical can be dangerous," he said.

However, as the rates of asthma and some cancers grow, researchers look at the proliferation of toxic chemicals as possible causes.

Since 1996, the federal Environmental Protection Agency has slowly been re-evaluating some pesticides for health risk. On Aug. 2, the EPA banned or restricted use of two pesticides used by apple growers, in part because of fears that they could cause neurological damage, particularly in children.

A recent study by the Washington Toxics Coalition sought to identify pesticide exposure to children in a survey of 33 urban and rural school districts. They found that 88 percent of the districts used pesticides on school grounds and only three districts warned parents before their application.

Elizabeth Loudon, pesticide policy analyst at the Coalition, said parents and school districts were concerned about the findings.

"We know that children are at a much greater risk for suffering harmful effects of pesticides," she said. They are more likely to digest or come in contact with the chemicals when they play.

But the causality between the dangers of pesticides and human health are still unresolved, said Robertson, the director of the Washington Poison Center.

"The presence of a pesticide doesn't mean it's going to make anybody sick," Robertson countered.

However, Paladin traces his fragile state of health to a pesticide spray used to kill wasps discovered in his Ferndale classroom. When he returned the next day, he experienced panic attacks, blurred vision and a burning in his chest. Paladin changed schools and recovered from this exposure, but routine pesticide treatment for ants at his new school eventually made him debilitatingly ill.

There was another individual with MCS in the Ferndale district -- a 7-year-old boy who also had to leave, opting for home schooling.

"There's a whole slew of us in society who can't function" because pesticides continue to be used, he said.

Jennifer Kropack has been luckier than many MCS sufferers. In 1997 she became sick from chemicals used in the remodeling of her work site, but was able to continue working from home as a water quality specialist.

At first, her co-workers, including scientists and engineers at the state Department of Health, were dubious of her claims.

"They couldn't even look me in the eye, they couldn't even talk to me," Kropack said. But acceptance of her illness has increased.

"I think it's been a learning process," she said.

This learning process has required people around Kropack to realize they must use certain deodorants and laundry detergent and forgo perfumes if they want to be around her. She carries a change of clothes washed with unscented soap that friends or family can put on if she reacts to them.

But MCS skeptics caution people against changing their lives and abandoning pesticides and other chemicals at the behest of MCS sufferers.

Cindy Lynn Richard, an industrial hygienist and consultant with the Maryland-based, industry-supported research group Environmental Sensitivities Research Institute (ESRI), said that without scientific evidence showing that certain chemicals cause specific illness, pesticide and chemical use should be allowed.

"We don't have a cause-and-effect relationship," she said. "There comes a point at which you need to weigh what is reasonable for a community and what is reasonable for an individual."

Richard said a community can start down a slippery slope, complying with MCS sufferers' demands, from elimination of pesticides to bans on certain paints and even restrictions on auto exhaust.

"At what point would enough be enough," she asked. With the limited scientific information available for MCS, how could you even document what was helping people, she said.

ESRI, a non-profit group whose supporters include the Cosmetic, Toiletry and Fragrance Association, Proctor & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive, provides modest research grants for studies of chemical sensitivity.

Dr. Barbara Sorg, a scientist in Washington State University's Program in Neuroscience, received a $10,000 grant from ESRI to support experiments in rats that try to simulate aspects of MCS, particularly heightened chemical sensitivity, a controversial trait of the disorder.

Sorg repeatedly exposes rats to formaldehyde to try to duplicate the sensitivity that might be occurring in humans. Once sensitized to one chemical, the rats, like MCS patients, demonstrate an increased sensitivity when exposed to other chemicals.

The research addresses one of the primary arguments against MCS -- the claim that there is no solid evidence that very low-level chemical exposures can make people sick.

Sorg has also found that the sensitivity appears to be permanent.

She is submitting her findings for publication in a scientific journal and has plans to test rats with other chemicals.

"I'm really in the middle" she said. If the disorder has not been thoroughly studied, it can't just be dismissed, she said.

Until there is an explanation for the diverse symptoms suffered by the chemically sensitive, whether MCS is one disorder or many, psychological or physiological in origin, the battle will continue over the ailment.

"The research is still not definitive enough to prove the existence of MCS," Paladin concedes. People with the disorder are "caught between the fact that no one really knows what is going on, but they're sick and people say it's psychological.

"If it's not part of your existence, you can't understand."

P-I reporter Lisa Stiffler can be reached at 206-448-8042 or lisastiffler@seattle-pi.com